Sunday Blog 195 – 27th July 2025

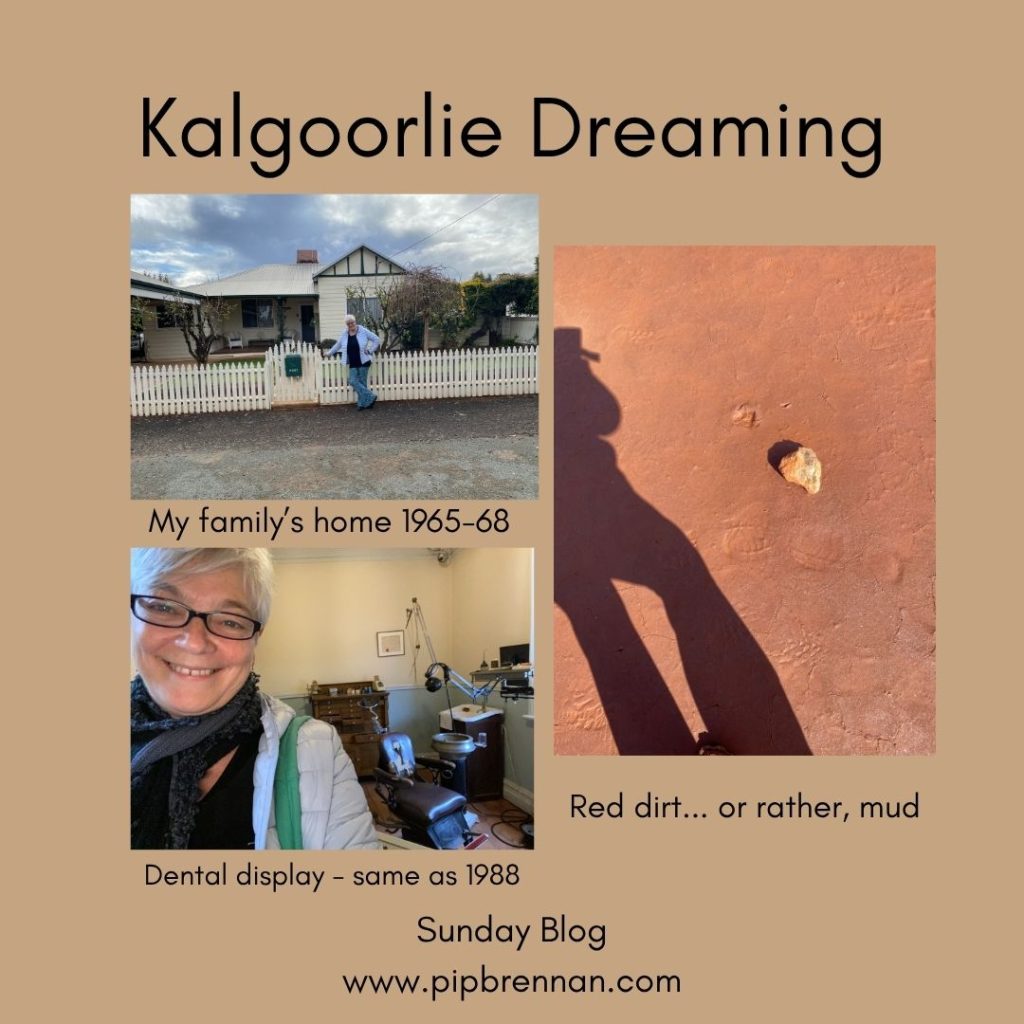

This week I had a mini-break in the mining town of Kalgoorlie, a 6-hour train ride from Perth. Kalgoorlie was my home from age 8 months to 3 years. No, I don’t remember it really. But I also went on several work trips there in 1988 and 1989 when I worked at the Western Australian Museum. So this week’s trip was a bit of an encounter with my young, ambitious 24-year-old self.

Initially hired in 1988 as the bright young thing who could explain the monstrous mainframe computer system to the History Department’s curatorial staff, I quickly pivoted. Given that I’d actually been employed to edit data files and write computer user manuals, I was always keen for distraction.

The History Department’s phone rang constantly with random, hugely varied questions about historical facts or perhaps an item they’d found in Aunt Doris’ attic they hoped was worth a fortune. I’d take down the complex queries, explain that I couldn’t advise them then and there, but would find out and let them know. Then I’d do some research, ask the curators for advice, and call them back. Often, people were crushed to know Aunt Doris’s old teapot might fetch $25 at best, or that a cherished story was just that, a story, and history had recorded otherwise.

Over time, my speciality became graciously refusing donations. By then I’d worked out that around of 90% of all museum collections sit in storage. Generally, whatever the donation was, we already had it in plentiful supply. People would turn up without an appointment, clutching their Mrs Potts iron they’d discovered in the shed. They dreamed it would be on permanent display, with their family’s name emblazoned on a brass display label forevermore.

I’d have to explain that we had several of that very same item already. I’d enlighten them about the shelves already groaning with items that wouldn’t ever see the light of display. I explained the heinous cost of museum storage, and how we had to reserve it for unique items. Then, I’d suggest the Education collection, where items that hadn’t been consecrated by formal museum accessioning processes could be handled and enjoyed by the students.

Usually the donor would be relieved that they wouldn’t have to carry the heavy item back home, and also feel virtuous they weren’t wasting taxpayer’s money with another surfeit collection item.

“It’s another Mrs Potts iron,” the senior curator would say to me. “You’ve really got the knack of gracious donation refusal. Would you mind?”

Getting the Kalgoorlie exhibition project in 1988 was a real coup for me. The Senior Curator whose vision it had been, had fallen pregnant unexpectedly and no-one else wanted the gig.

Each and every day I said to myself “well I’ve never done this before, but it doesn’t mean I can’t do it.”

Some of the exhibits I worked on back in 1988 are still there today. I think I can trace my handiwork, from when I helped gloss the wooden skirting boards of the old British Arms building for phase one of the project.

Phase two in 1989 was installing displays in the newly built modern museum adjacent to the British Arms building, known as the smallest pub in the Southern Hemisphere. My inexperience meant I made the rookie mistake of choosing items that sounded important on paper, but were dull to look at.

So the newer gallery displays from 1989 have been significantly changed but some items threw me right back to when I was one of the exhausted, exhilarated installation team. We got the galleries done in time. Just.

My personal involvement aside, the museum of the Goldfields is definitely worth a visit if you’re in town. The downstairs galleries change regularly and the current audio visual display to celebrate and preserve some of the many Aboriginal languages of the area is a must-see.

And for me, the chance to catch sight of my cherished colleague Julia Lawrinson’s Trapped in the shop was another bonus.