It was the third time he’d approached me in two hours. I was scratchy-eyed and still unclaimed, waiting at Thessaloniki airport from three o’clock in the morning. A particularly charmless airport in Greece’s second-biggest city, six hours north of Athens. He was yet to find the person he’d been tasked to meet, or so I gathered through our pantomime interaction. I had reached, then surpassed my thirtieth year without finding the right man in my life, and it seemed sensible to throw in a good job in the museum sector and try my hand at English Language teaching.

So here I was after six years, yet another Australian in London, moving to Greece, with perhaps two words of the language under my belt. I’d finished a month-long teacher training course the week before. Mortgage payments pressed in on me from the flat I’d left behind in London – there was no time to delay, another job must be found. Greece was willing to take me with my thin credentials, so here I was. Apartment included.

The red-eye flight had been paid for by the tin-pot private English school I’d be working for, a fitting start to the quest (or ordeal?) that was ahead. I was due to be picked up at 5.30am by the school owner’s daughter, Katerina, and just had to while away the intervening 2.5 hours, longing for bed and repeatedly repulsing any efforts of this strange man to cart me off. I shook my head again at him, not realising that a different head gesture was called for to convince him of my denial. I was yet to understand that indisputable Greek no that looks like a gesture of disdain. I needed to thrust my head and eyes upwards, making a single “tsk” sound. Then he would have been in no doubt. But I shook my head with cultural ineptitude, and he kept returning.

The clock crept forward to 5.30 am and finally Katerina appeared, a young, dark-haired woman accompanied by a tall, blond and fleshy consort, the boyfriend. Kristos I think, the name wafted away before I could catch it. Meanwhile, he took the handle of my suitcase from me and we marched behind him to the car.

It was noticeably warmer than London, once outside the airport. In the car, I struggled to get a sense of this new home as we travelled the ring road around the city. The street signs showed destination names first in Greek – large lettering- then in English spelling, smaller – a necessary if reluctant concession. None of the names meant anything as they loomed up then fell behind the car. I knew little of this ancient city, founded in 315 BC and perhaps most famous for Paul’s Letters to the Thessalonians. Once its skyline boasted minarets galore, but once the city returned to Greek hands, most remaining minarets were demolished and silenced.

The conversation had the stilted formality of strangers jammed into a car together. Katerina’s English was heavily accented but fluent, Kristos (we shall call him then) threw out some words of English, harder to understand as they were more caught up in an impenetrable accent, and he clearly didn’t have her proficiency.

We turned off the ring road and the city began to reveal itself bit by bit. Perhaps too many trips to Italy had led me to expect something gracious in the buildings – not this endless expanse of almost identical concrete apartment blocks, with their ugly awnings and charmless street-level shop fronts. I mean endless concrete. Its sparse ancient ruins were lost within this sea of concrete, just flashing out here and there with sudden grace. A city wall, a remnant of an old church and then it was gone, sucked into the Greece Anywhere vortex of Soviet-style apartments.

Kristos suddenly halted his car at one of the incomprehensible shops and proudly announced that without delay I was to sample Thessaoloniki’s finest bougatsa – pie. He especially recommended cream pie, which at 5.30 in the morning was the last thing I wanted to face. I longed for a shower and some solitude from the press of politeness, and perhaps a cup of Earl Grey tea and milk.

Our conversation grew if possible even more stilted, as Kristos, released from the chore of driving could turn his attention to murdering the English language more thoroughly. Eventually, having satisfied his substantial pastry cravings (I nibbled at a spinach pastry while he wolfed down endless triangles of oily pastry with a sliver of cream sandwiched between the crusts) we returned to the car.

We passed street after street, all an identical and disorientating blur until the car stopped again, but this time Kristos announced we were at the school. I murmured admiration, listened carefully to Katerina’s instructions on how to walk from the school to the apartment, and reiterated them as we drove the same route to the apartment. Finally, finally we made it there. I sounded as confident as I could about the directions, knowing I would have to strew breadcrumbs all the way in order to find my way home again at the end of the working day.

Katerina opened the door to the apartment complex and Kristos lugged my suitcase up the two flights of stairs despite my weak protests. A wooden door swung open to reveal a surprisingly light and pleasant interior, perfectly camouflaged by its concrete exterior. Perhaps a good landing spot after all?

She advised me my flatmate, who had arrived the day before, was still asleep. She gestured to my room, gave me my copy of the keys and they vanished into Sunday.

In the silence that followed I crept like a burglar to the kitchen, opening the fridge door gingerly, spying items I didn’t quite understand. I couldn’t know then how I would discover the glorious, thick Greek yoghurt, how well it blended with nuts and honey. How good the tomatoes at the corner shop would be, and fresh flat-leaf parsley I would at first mistake for coriander.

But now I was prowling around, waiting to meet my new flatmate and feeling much too old for house-sharing with strangers. It had been some years since I had consented to live with someone I didn’t know, and I was far from sure that this would be a trend worth breaking. I unpacked, washed, lay down and read.

Sleep had overtaken me when at about 10am I heard stirrings and got up to greet my housemate. A fresh-faced, youthful blond woman emerged from her room, a good decade my junior.

“I’m Emma,” she greeted me.

“Lovely to meet you. I’m Pip.”

We launched into the inanity of first conversations and by the end of half an hour I allowed myself a hint of relief that this seemed doable. Sure, I felt old, I was old for this kind of venture. But I was here, I needed to make the best of it and my flatmate seemed a good sort.

Lured by the unknown, we ventured out together into the incomprehensible streets – her school was just across the road, whereas mine was further away, down the street. I surprised and delighted myself by being able to find the school again and we walked past it.

Emma knew all sorts of things I didn’t, including that there was another pair of English teachers living closer to the centre, and we continued walking past the school, down the steep hill to find their house. One of them, Sarah, had lived at our apartment, taught at the school Emma was about to start in. The other, Bec, had lived in a small Greek village with her lover, but they had split, and she had retreated to the relative safety of Thessaloniki.

They welcomed us in and shared tales of the school Emma would be teaching in – not encouraging – and warnings about Katerina’s mother, Kiria Sonia who ran the school where I would be teaching. A cold hand clutched at my will, squeezing out all the juice, courage and vigour of my career change adventure.

All four of us went to the nearest taverna for a 3pm lunch and I promptly fell in love with the wonders of Greek cooking. All garlic and olive oil, what was not to like? Bec and Sarah warned us that food would come out in any order, and that all plates were shared. We had forks to dip into the shared plates of goodness. The reticence of six years in London was sloughing off more and more with the intimacy of this eating style. We washed down the heavenly food with retsina, like cheap white wine laced with pine household cleaner. I was advised it was slightly better with a dash of coke. Ewww. But it was, kind of.

We four women were outnumbered by the old men that sat about the taverna, twiddling their worry beads, clicking at backgammon, talking loudly to each other. Bec was awash with indignity about the selfish cruelty of (all) Greek men, savouring her release from the village and doomed relationship.

Bec’s timely warning would not have the desired effect of preventing Emma and me from having skirmishes with Greek men, as alas, most of us cannot heed the warnings that would save us.

But that first night of innocence and novelty, as Emma and I wobbled back up the hill home, the glory of Thessaloniki revealed itself in mountains on the horizon, backlit by a beautiful sunset. We stopped and admired several times.

Plus, we couldn’t believe how easy it was to access cheap cigarettes and alcohol around the clock at the kiosk-style peripteros, and we bought just a few beers to finish off the evening as it was off to work the next day.

There was something special about being dressed for a day’s work, satchel swinging jauntily in hand as I headed down the hill. To be in a country where you had no idea where you were, could not even have the simplest conversation, and yet to be gainfully employed, what an exciting privilege. So superior to being a tourist.

As I approached the school building I saw Katerina waving at me through the window, then heard a piercing voice calling out Katerina’s name. She smiled at me briefly, indicated the seat I could wait in before scuttling in to hear her mother, Kiria Sonia’s commands.

Her mother’s seat of power was a glass office that allowed for everything to be monitored.

“My mother is ready to see you now,” Katerina re-emerged from Kiria Sonia’s lair, motioned for me to enter.

A woman with cold green eyes, a large, light-brown bouffant hairstyle, chunky jewellery, an arresting patterned, shoulder-padded business suit, and significant amounts of makeup sat in a chair behind the desk. A pampered pooch also eyed me coldly, a threatening growl emitting from its miniature body.

She held a cigarette holder in her right hand, the cigarette smoke spiralling from its end. Her eyes never left mine as she drew it to her mouth, inhaled fully, then exhaled an impressive cloud into the smallish office. There was absolutely no hint of a smile. She finally spoke.

“Whhelcome.” The word whirred out of her in a Greek flourish. Nothing in her tone or her eyes indicated any sincerity in the sentiment.

“Hello,” I answered with manufactured bravado and a smile, just in case it worked. It didn’t. She drew on her cigarette again, still fixing me in her stare, weighing me up, finding me wanting. A pause, another exhale.

“What is your name?”

“Pip,” I answered. Then in the pause, said “Pippa” as this is sometimes easier for people to understand.

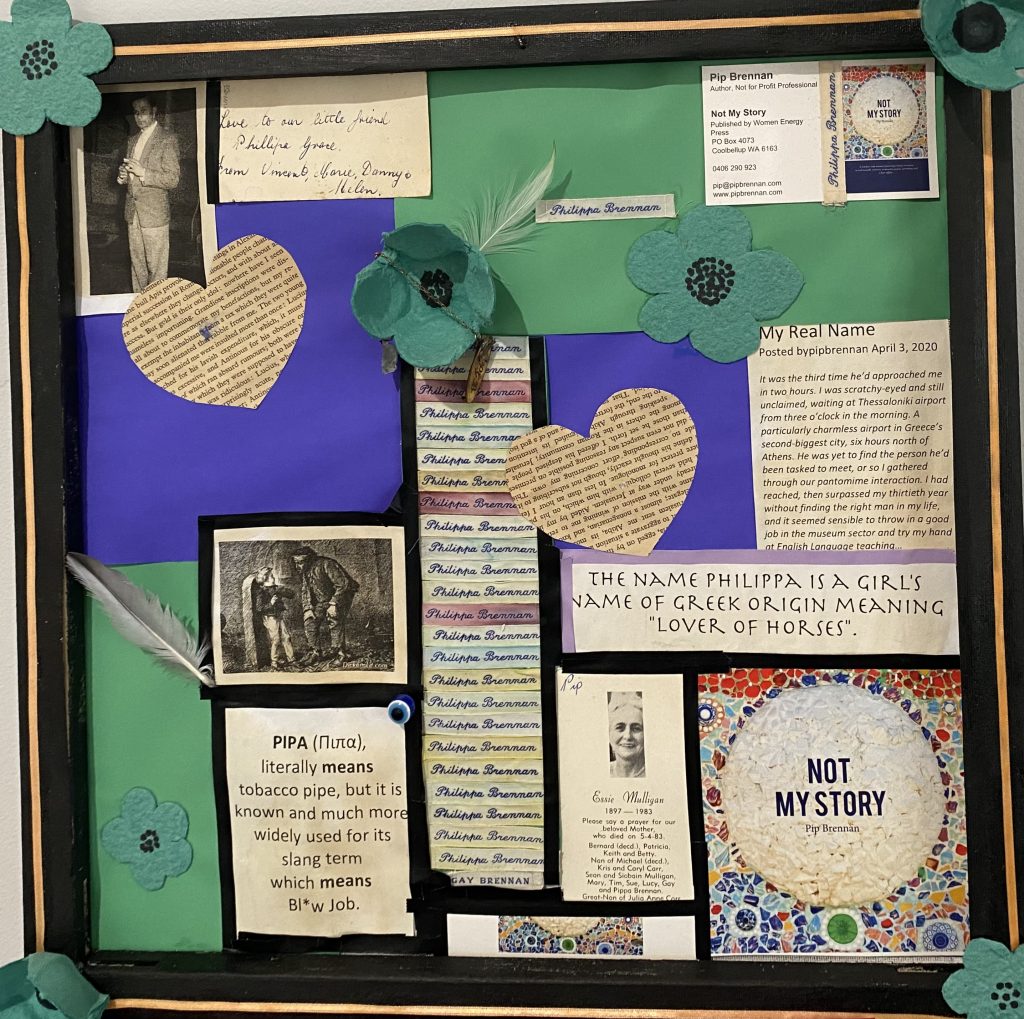

If anything, the look hardened as she drew yet again on her cigarette. Perhaps this cloud of smoke was even bigger than any other emitted as she asked, “Do you hhhave real name?”

“Philippa.” How I hate this full name, only used in my childhood by my parents when I was in trouble. I have always been known as Pip. She continued to fix her green stare on me, inhaled again. On the exhale, the small room by now having more carbon than oxygen, she announced;

“We will call you Philippa.”

I agreed immediately, I could not imagine any course of action other than complete submission. I endured further questioning about my credentials, then Katerina was brusquely summoned to fetch me for my orientation.

She proudly showed me the new textbooks I would be teaching all year and I looked at their amateur drawings and clunky exercises with dismay. Here it was, the dislocation that comes to those fresh from study and theory to reality. The textbooks were completely different from the pedagogically recommended kind, the classrooms had bolted down chairs and desks, making it impossible to undertake the many different interactive language learning activities I was trained to facilitate. But then, it had been a four-week course on how to teach adults English as a Foreign Language, and here I was, facing 7 to 16-year-old Greek children, with zero parenting or crowd control techniques. What could possibly go wrong?

Katerina advised me that there were in fact two small schools, and I would move between the two to teach my classes. My timetable was produced, and here was an incredible stroke of luck. There were just 12 contact hours of classes due to low enrolments, but my contract was for 20 hours. I would make up the time with whatever was required – marking, administration, anything. I was permitted to prep for my lessons as well in this time after everything else was done. As such a greenhorn teacher, it took me several hours to prep for each one-hour lesson, so I was indeed a very lucky person. Like a sort of cosmic trade-off for having scored the school with Kiria Sonia at the helm.

Katerina took me to the second school building, a humbler one with no Queen Bee office or fancy reception area, just a simple desk. She introduced me to the Secretary, Anna, and left me with a pile of tasks to complete. Anna began to ask me questions in the space that Katerina’s departure created.

“Hhow old you are?” Anna asked.

“32” –I never dissembled about my age, but truth be told, I was smarting from my lack of marital and maternal status.

“And whhere is your hhusband?”

At such a direct invasion of my privacy, there was nothing left to do but look behind me to the left, to the right, and then say, “He was here a minute ago Anna, but he seems to have disappeared.” We laughed and I clung to this little piece of kindness and informality. We would have many cozy chats over the coming year when others weren’t listening. She was not so unfortunate to be boyfriend-less, and together we dissected and analysed many an interaction with Babbis. He sounded like a pill. Anna’s life was given meaning by George Michael, still very much alive at that time. She was not at all dissuaded by his stated preference for men. When she met him, he would finally understand what sex was all about.

Emma and I compared our first day at our respective schools and I could answer with some honesty that it hadn’t been too bad, apart from being renamed Philippa. Emma was incredulous at my lucky break of just 12 contact hours, her dance card being completely full – 20 contact hours.

Life became a series of baffling encounters, like the lung X-ray all new teachers needed to have taken, as we were Aliens in Greece. Kiria Sonia’s son took me on the back of his moped to an appointment at a hospital at a very inconvenient distance away from the school. He barely deigned to talk to me, being five years younger and having a just-so Jesus beard to mirror his mother’s views of his perfection. But he was a competent translator, and eventually, we sat in the waiting room of the physician who was perusing my lung X-ray, looking for alien diseases. He barked at us to enter the room, and casually smoked his cigarette as he gave me the all-clear for my lungs. I had known that Greeks smoke everywhere, I just didn’t think they would smoke everywhere. Clearly even the medical establishment thought the links to cancer were spurious.

The school opposite our apartment had a very loud loudspeaker, and the children would chant something every day. Many months later I found out it was the Lord’s Prayer – it had a jaunty, repetitive cadence in Greek.

But perhaps the most baffling encounter of all was my very first Parent Night at the school. There I was, very uncertainly having to talk to parents about their little darlings, using strings of inanities and grappling for some kind of meat to put on the bones of my sparse summaries of their children’s stumbling English. I then had the humiliation of standing by while a poor colleague translated my inanities into Greek. I could only hope she added in something more useful than whatever I had said. Kiria Sonia looked on at us all from her glass throne room to complete my discomfiture.

While I wasn’t sure of the exact issue – best guess was a student accused of cheating – and the indignant mother entered Kiria’s throne room and began shouting. Kiria Sonia leapt from her chair, also shouting. The two carried on their din, moving into the foyer where we teachers and parents milled. There was no privacy or shame in this display of mutual rage. Instead of placating the indignant mother quietly and containing and dismissing her, as would have happened in England, here it was a Greek slug-it-out shouting match for all to see. My colleague was now having the put her lips right up against the mother’s ears as she translated my nonsense. The show had to somehow go on. The indignant mother suddenly retreated, and the cyclonic storm ceased. I held together my shredded nerves for the rest of the Parent Night, seemingly alone in my perturbation.

Such displays fuelled my fear of Kiria Sonia, and I was always eager to escape to the second school building where she couldn’t see what was going on. I had dubbed Kiria Sonia The Gorgon. The unsmiling, stone-inducing green eyes had not softened at all towards me, no matter how I toiled at my lessons and marked endless exercise books.

Meanwhile, after hours, Emma and I had found the ex-pat community and the right bars (such as the subtly named Boozer) and tavernas, familiarised ourselves with the main streets and waterfront walkway. We made the best of the beautiful ugly city that is Thessaloniki. Entertainment out of home was a must, as Greek television was almost universally bad. If you liked either subtitled or, even better, dubbed Chuck Norris or Bruce Lee movies, you were in luck. Soaps were also very popular, the kind where the set really does look like it will wobble and fall if any of the coiffured stars venture too close. Often there were long airings of obscure gymnastic competitions where station owner Kostas’ daughter twirled and stumbled across the mattresses. Soft porn was there too, just to mix things up, but mainly it was American movies and sit-coms with Greek subtitles. English and inanity constantly poured out of Greek television sets.

So I rarely bothered the television. Except for one night, about three months after my arrival, I found myself watching a ubiquitous American movie with Greek sub-titles. I had elected to stay home while Emma was out for another punishing night at Boozer. Surely the TV wasn’t that bad? I found a watchable American movie and entertained myself by trying to practice my fledgling Greek to read the subtitles. While they often lagged a little, it was unmistakable. The American actor had used the word “blow job” and there it was, the Greek word for blow job. Pippa.

Sure, The Gorgon was not friendly by any stretch of the imagination, but if it was not for her, I could have walked into a classroom of 14-15 years (eventually known as Bastard Class) and gaily announced: “Good morning, I’m Miss Blow Job and I’m your teacher for the year.”

Oh Pip just loved reading this! Brilliant poignant funny!!! I hope there is going to be more instalments🙏🏽