Sunday Blog 153 – 22nd September 2024

One of the absolute wonders of travel to me is that I can be me, but somewhere far from home, if I just travel enough miles. And since Wednesday, I’ve travelled 17,000 kms/ 10,563 miles. The I, the Me that is housed in my body can find itself on the other side of the world in a new bedroom, looking in a different mirror as I clean my teeth, rolling out the yoga mat on a new floor in the morning. The magical time travel effect is heightened if I return to a place I’ve been before. There I am again, the same but different.

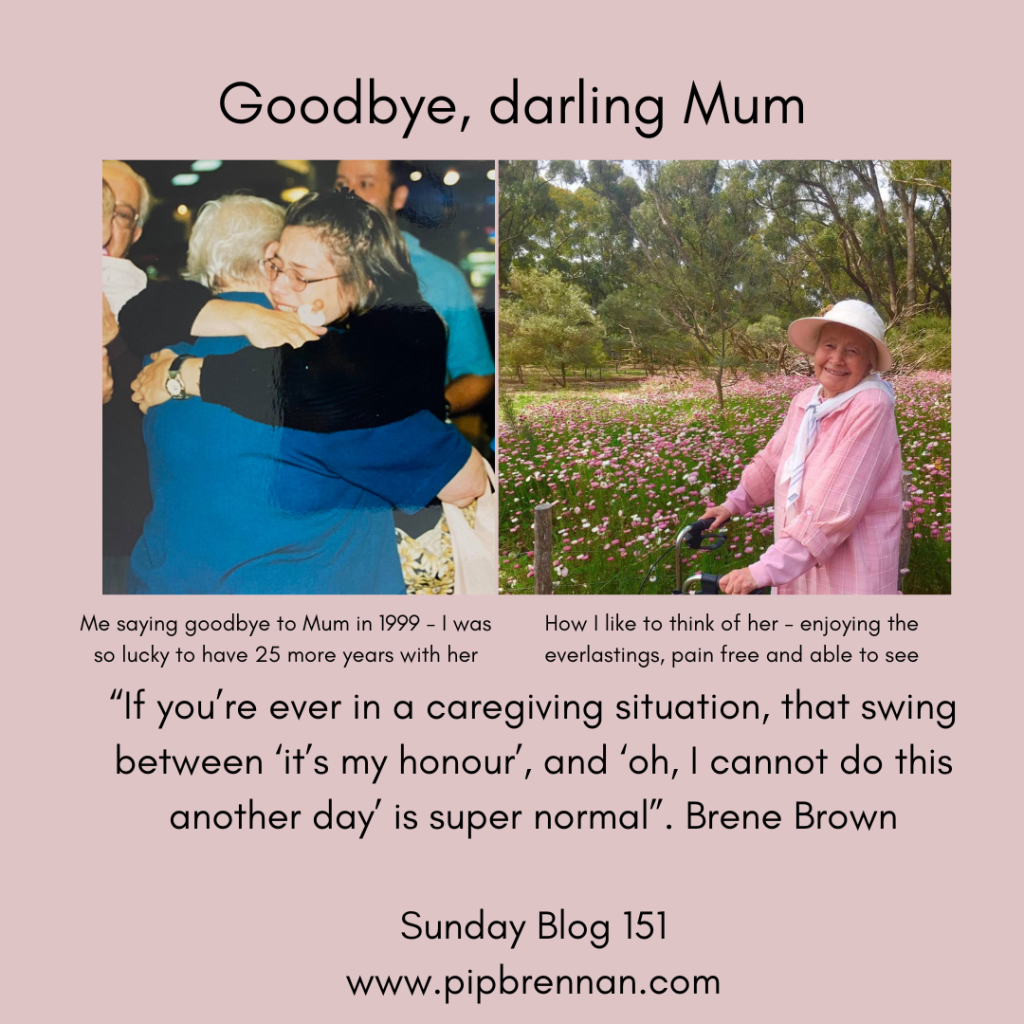

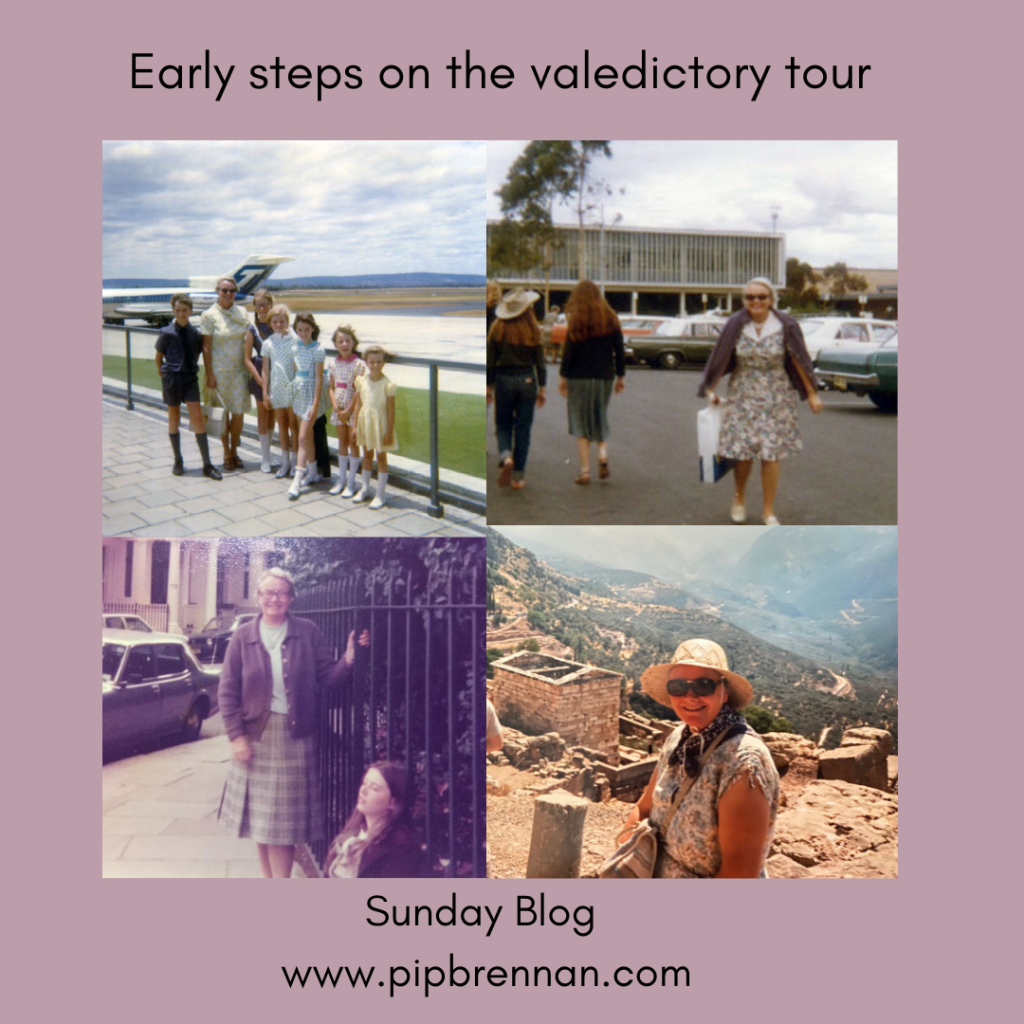

- Top left is the 1975 photo of us in our finery to see my uncle off on his European travels. I’m the smallest one on the left. What an occasion this seemed to us!

- By 1978 my brother left on his odyssey to India, South Africa and the UK, and the top right image is the one he snapped of Mum, looking for all the world to be excited. In truth, she hated it when any of us left home.

- The bottom left shot is Mum and my exhausted sister Gay in London. After the very first long haul flight we’d endured, we were turned away by the cabbie in Victoria station and had to walk with all our suitcases and completely inappropriate foot wear to an uncertain destination. At a certain part of the trudge, I think it was my brother who again snapped this shot of Mum looking very happy despite the elusive bed and breakfast. She was a driving force in planting the travel bug in us all. Her entire salary as a teacher librarian was set aside for several years to finance this 1979 European trip.

- In the late 1980s she got to enjoy some child-free travels, including Delphi, the image on the bottom right.

Travel beckoned to me but also challenged me from a very young age. One particularly traumatic airport farewell with our brother in 1979-we were leaving him in London and didn’t know when we’d see him again-put me off for some time. I cried the entire long haul flight back to Perth. Travel is destructive, my fourteen-year-old self had decided. It causes painful separations.

Predictably by adulthood I’d coarsened any such sentiment about family separations, and left in 1990 for a two year working holiday in London. This stretched into a decade, during which I only saw Mum a handful of times. The moon was one of our ways to stay in touch. I’d look at the moon, she’d look at the same moon on the other side of the world. We did have letters and phone calls, but the moon felt like a direct line to each other.

I boarded the plane from Perth to London on Wednesday this week for my working/ writing/ yoga/ valedictory tour for Mum exactly one week after her funeral. The full harvest moon as the plane took off was breathtaking, but resisted all attempts to be captured in a photo. It was there to greet me at moonset in London just over seventeen hours later.

And here I am, walking through faraway places I’ve been before. I went down the very London street where Mum is looking triumphant while sister Gay sags against the railings. I’m now in Greece, back to the retreat centre I last visited in 2019. But everything’s changed without Mum in the world.

This phrase from favourite book kept nagging at me so I’ll let E.M Forster have the last word.